Cloth, Culture, and Sustainability: Ifebuche Madu’s Vision for African Textiles

On September 27th 2025, the doors of Red Door Gallery opened to a world draped in cloth. Visitors stepped into an exhibition where fabrics told stories of history, indigo blues, earthy browns, hand-woven threads carrying the weight of centuries. The show was titled In the Beginning, There Was Cloth, and at its heart was Ifebuche Madu, the woman who has made it her mission to stitch Nigeria’s textile past into its future. For Madu, textiles have never been mere fabric. They are archives. They tell of women who bent over dye pits under a blazing sun, of weavers who translated community and identity into patterns, of stories knotted into cotton long before books arrived.

Her journey into this world began not in glossy fashion studios but during her youth service in Ondo State, where she first encountered Adire makers at work. Watching them dip cloth into steaming indigo baths, she understood that these crafts were more than decoration; they were survival, resilience, memory. But she also saw how fragile they had become.

That realization grew into Afrikstabel, the company she founded to preserve, modernize, and globalize Nigeria’s indigenous textiles. It is less a business than a movement. Today, Afrikstabel supports more than 150 artisans across the country, with a network that has created over 2,000 direct and indirect jobs. More than 92 percent of these artisans are women, many of whom once feared their skills would die unrecognized. Instead, they are now part of a growing enterprise whose fabrics have found their way to at least eight countries. Along the way, Madu has trained more than 560 youths, ensuring that weaving and dyeing remain living skills, not relics.

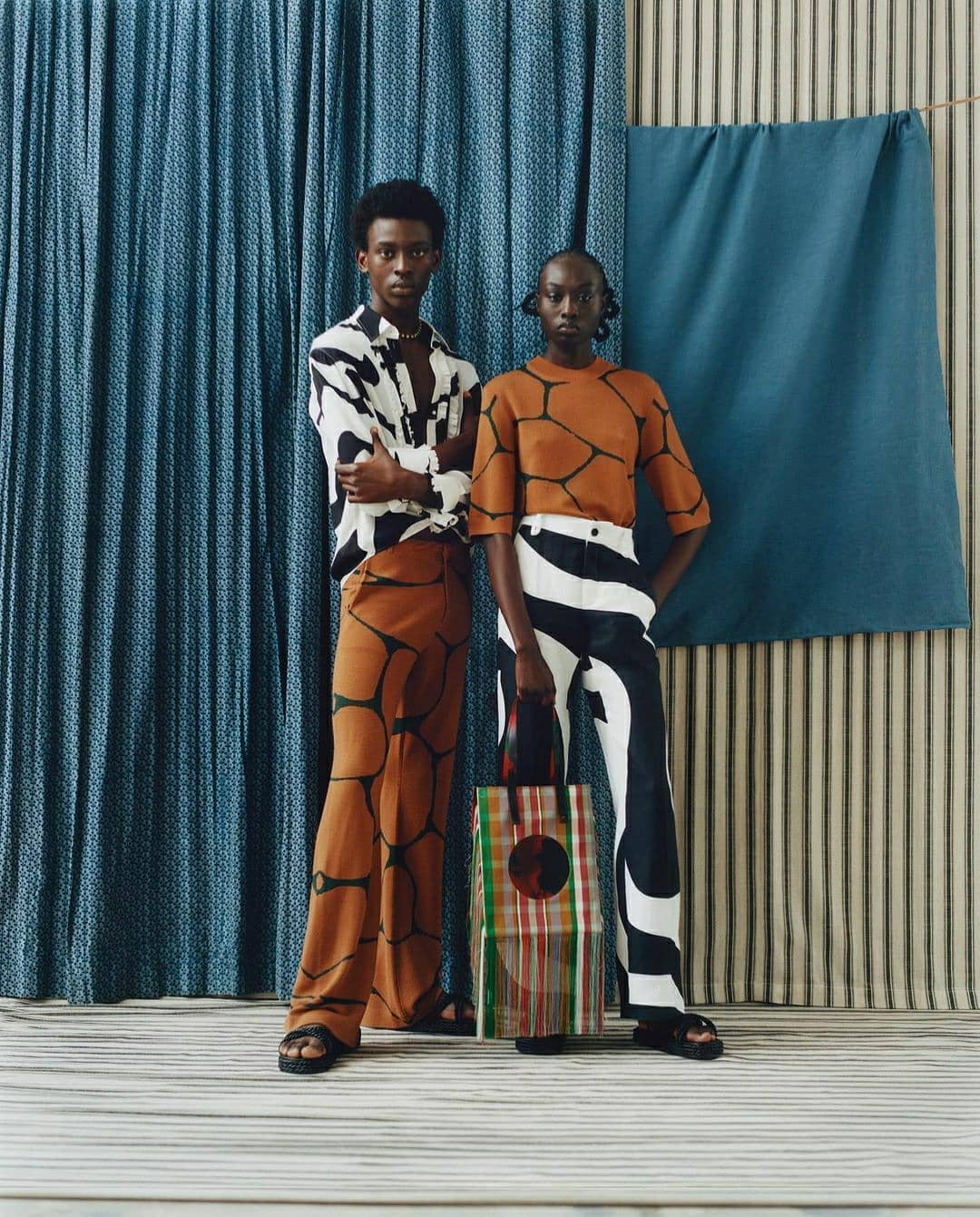

Her work is not romantic nostalgia; it is a reinvention. In an era when fast fashion churns out lifeless prints, Afrikstabel insists on slowing down. Fabrics are made to order, designed in collaboration with clients yet rooted in heritage. Each cloth carries the fingerprint of human effort, a testament to process and patience. It is fashion as storytelling and the world has begun to listen. When Nigeria’s Olympic delegation stepped out in green Adire during the Games, it was Afrikstabel’s artisans who had dyed the cloth. To the athletes, it was uniform; to the audience, it was spectacle; but to the makers, it was visibility at last.

Yet preservation comes with challenges, especially environmental ones. The indigo vats of Adire dyeing often leave behind toxic wastewater, a problem many producers quietly ignore. Madu refused to look away. Instead, she spearheaded a self-funded wastewater treatment plant, a groundbreaking step that allows her team to dye responsibly while protecting the land and water around them. In her world, sustainability is not a buzzword; it is a promise to both the planet and the people who depend on it. This balance of heritage and innovation came to full bloom in the September exhibition. In the Beginning, There Was Cloth was not a simple display but an immersive exploration of Nigeria’s textile history.

Alongside fabrics were a short documentary and a coffee-table art book, curated in collaboration with historian Oludamola Adebowale. Here, Aso-oke sat beside Akwete; Adire unfolded its indigo secrets next to Uli motifs. It was an attempt to show that cloth is not just craft but script, that it encodes identity as surely as language does. For many visitors, it was the first time they saw textiles as more than fashion, they saw them as heritage.

Walking through the gallery, Madu did not play the role of a distant designer. She spoke softly with visitors, explaining the symbolism in motifs, the back-breaking labor behind dyeing, the way communities live inside every thread. She moved not as a businesswoman chasing trends, but as a custodian determined to ensure that these traditions outlive her. Her story is not finished. Each yard of cloth that leaves Afrikstabel is both product and prophecy: that Africa’s textile legacies will not be forgotten, that artisans will not fade into obscurity, that the world will come to recognize cloth as history you can wear. Ifebuche Madu is not simply making fabric; she is weaving memory into the present. And as Lagos’s gallery walls proved, the story of cloth is far from over in fact, it is only just beginning.

Comments